Improving COGS Horizontally Across the Supply Chain

Driving value for all trading partners and achieving least landed cost

Customer demand is power. This power has been used to negotiate pricing from a purchasing perspective for many years. However, as we experienced in the pandemic, this power was short-lived without visibility and control across all trading partners – upstream through the supply chain network -where each participant plays a role in making and delivering product for the end consumer.

In the past, this problem was more manageable as retailers and brand owners also owned the upstream assets to create products. Today, most demand is owned by the retailer, the brand owner, or the e-marketplace consumer from an omnichannel perspective (depending on how retail or the omnichannel is structured). The balance of the supply chain network is outsourced to trading partners.

The challenge in this case is that the physical supply chain is outsourced to a network of providers. The risk to sustaining the power of owning consumer demand is, however, now dependent on the outsourced network to meet that consumer demand. Without direct control of the upstream supply chain, this puts every company’s brand, product, and shareholder return at serious risk. The company that can optimize their end-to-end business network will win. Those that can’t will go away.

Retailers and brand owners continue to strive for improvements in landed costs. Given they no longer carry the inventory, carry the capacity, or control the assets in general, how then can they influence the landed cost?

One way is through mandate. Walmart recently imposed a requirement for 98% On time In Full (OTIF) compliance, where a violation has the supplier potentially hit with a 3% COGS chargeback. This level of performance (as compared to typical industry performance which is in the 80’s) would drive additional revenue and margin per square foot at the shelf, along with reducing the days of supply required to keep the shelves fully stocked.

Problem is that the supplier base views the mandate by Walmart as cost-shifting to where they will need to carry more inventory for a higher mix of products than in the past, along with absorbing expedited and premium freight costs to better manage demand and supply variations. In other words, this could be a win-lose situation for the retailer and the supplier. In the age of sustainability and shifting market dynamics, win-lose is suboptimal. The minute a supplier of a top sell-through item for the retailer cannot afford to produce the product, the game shifts to lose-lose for all parties.

On a network the opposite is actually true. A win-win-win situation is achievable, where the retailer wins with margin and market share, the suppliers win with lower operating cost and better trading service, and the consumer wins by getting the best product at the best price on demand.

A Win-Win-Win in CPG. Take, for example, the proven case study of large CPG manufacturer who was meeting retail service level needs by carrying 65 days of supply from the shelf upstream through manufacturing, which is typical of most large CPGs. This firm planned and scheduled using the typical static lead times for both orders and logistics that are part of an ERP deployment, along with significant information latency among trading partners, given that everyone wants to run a local optimization prior to passing new data/information to the next node.

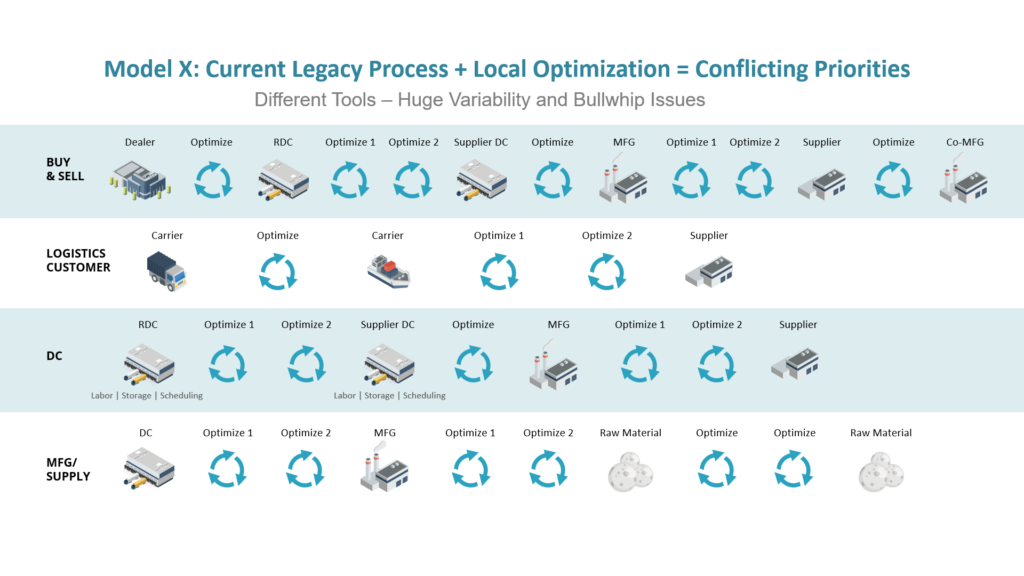

In this typical network, there are 21 competing optimizations running from the end-consumer upstream through the supply base, as seen in Model X. Promotional in-store/in-stock was only running at 80% and with 40% of revenues being driven through promotions, the opportunity for improvement was tremendous.

The trading partner ecosystem was migrated onto One Network and the results were impressive. Promotional in-stock rose to 99%, thus achieving significant value as compared to the prior 80%. And this was achieved while also lowering inventory from 65 days to 25 days, as well as reducing the number of planners from 13 to 6.

The only way to solve for improvements in least landed cost while also increasing customer service levels is to move to a network. Otherwise, even though you may own the demand, without a real time demand-driven trading partner ecosystem, each part of the network is waiting for information from the next tier to start action. In other words, no one will be moving across the network in real time, and so you will not be able to collaborate across planning, scheduling, and execution processes with the trading partners who own the COGS — and thus are the only ones who would be able to effect real cost savings.

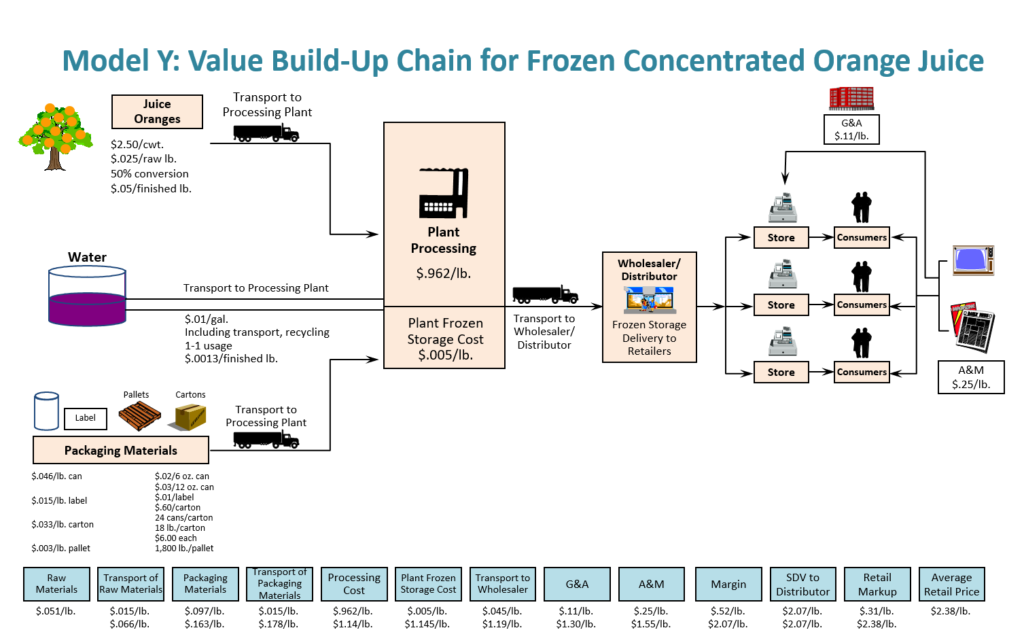

Unlocking Value in the Food Industry. Some of you may remember the movie Trading Places where the commodity trading was focused on frozen concentrated orange juice. Why does frozen concentrated orange juice average about 2.38/lb at retail between branded and white label? All we need to do is look upstream in the supply chain to see the cost build up per supply chain network. As the retailer/brand owner you seemingly have all the power. However, in looking at the value chain, you are somewhat limited to purchasing negotiations, base, lift, G&A, some marketing/advertising and your markup. If you just try to squeeze your upstream trading partners through purchasing, are you really driving long term and sustainable value across your partner ecosystem?

Bringing your trading partners onto the demand-driven real time network is the true way to amplify your power of demand. In one fell swoop, you will eliminate all the information lead times, local decision making, second guessing, and bullwhip effect which is a result of Model X.

For our food network (Model Y), the upstream cost/lb totals $1.19. At $2.07/lb in cost prior to markup at retail, this represents a whopping 57% of the cost.

Your ability to control Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) now extends upstream through your entire supply chain network. This is network opportunity. The power of demand must move past procurement/ price negotiations and into driving an ecosystem for trading partners across a real time demand driven supply chain network.

The earlier CPG example where inventory dropped from 65 days to 25 days as service levels increased, is directly applicable to our foods example here. The costs of excess inventory, lead times, capacity utilization, expediting, waste, etc. are all trapped in the $1.19. The impact of the inventory reductions alone can have a significant impact on this number. Retail markup is 31 cents. At just a 10% improvement on the $1.19, this generates 12 cents in savings. If half is shared with the trading partners and half with the retailer, this 6 cents for the retailer increases margin by almost 20%! Win-win-win.

In Summary

We learned many things about supply chain network resilience, business continuity, and operational readiness as a result of the pandemic. However, as we look deeper, the loss of visibility and control is just part of the problem. The ability to create a winning scenario for all the trading partners in our ecosystem is really the end game we should strive for, along with resource sustainability. Understanding your horizontal cost of goods sold and how to apply a real time demand-driven supply chain network end-to-end is the only way to generate shared value which is material to all trading partners.